I think that Orson Welles was one of the most fascinating people of the 20th century, and certainly one of the most misunderstood. Even more than twenty-five years after his death, the general consensus of opinion of him seems to be that he scared people with a radio play about Martians and made one great movie, then did nothing else of much interest for his remaining forty-four years.

I have seen seen eleven of Welles's twelve completed feature films (missing only the almost impossible to see

Filming Othello, his last completed movie), listened to a huge number of his radio productions, watched a lot of movies in which he appeared as an actor, read six biographies of him, watched at least three documentaries about him, and watched, read and listened to countless interviews with him. I feel as if I'm only scratching the surface of this remarkable, furiously talented man.

Welles is often painted as being undone by his own self-destructive tendencies and as torpedoing himself through his own fear of completion. This is pure myth. He was clearly rather undisciplined, and he doesn't seem to have been very good at raising money himself or picking commercial projects, but this was not his undoing. His difficulties in getting movies made were far more complicated than that.

A good example of how these myths can be knocked down is provided by the example of Simon Callow, a very distinguished actor and talented writer who is in the midst of writing a huge, multi-volume biography of Welles. The first two books in this series have appeared, and the contrast between them is fascinating. Volume one,

The Road to Xanadu, was written with the stated aim of not asking "What went wrong after

Citizen Kane?" but rather, "What went wrong before

Citizen Kane?" and provided a thesis that Welles had already demonstrated the traits that would become his own undoing by the time he made his remarkable first movie at the age of twenty-six. This book is highly critical of Welles and depends rather heavily on the unreliable accounts of John Houseman, Welles's first theatrical producer, an extremely valuable collaborator in his early years before their relationship unfortunately soured to the point where the two became bitter enemies.

The second volume,

Hello Americans, appeared eleven years later and this lengthy wait between volumes clearly reflects the heavy amount of work and research that Callow put in to it. Where the first book covered the first twenty-six years in Welles's life, this second volume covers a scant six years while having almost as hefty a page count. The book starts off with the real beginning of Welles's downfall: the production of his second feature

The Magnificent Ambersons, which may have been his masterwork before it was irrevocably mutilated by the studio with the aid of some of Welles's most trusted colleagues; and the closely linked disaster of

It's All True, the documentary he was convinced to make in South America for the war effort which both kept him away from being able to defend

Ambersons and the expensive collapse of which gave him the undeserved reputation of being frivolous and wasteful.

The other main focus of

Hello Americans is something that only Callow has investigated in depth, and that's Welles's political activities. He became heavily involved in progressive politics in this period, inspired partly by his friendship with US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and campaigned so heavily for issues raised by the NAACP - particularly the case of Isaac Woodard, a black war veteran who was savagely beaten and blinded by racist police - that he was hung in effigy in the American South. Welles ended up with a thick file at the FBI for his "subversive" activities, and his unalloyed passion for social justice made him more than a few enemies.

I recently watched a lengthy BBC documentary about Welles centred around a long interview conducted with him in 1982, three years before his death. Although by this time he was sixty-seven years old, had a white beard, and was immensely obese (which made him the butt of many cruel jokes), in his attitude and demeanour he seemed almost not to have aged at all for the most part. But when he spoke about the movies that had been taken away from him the weight of his years seemed suddenly to fall upon him, and his sorrow at their loss was so tangible it was hard to watch.

Despite all of these difficulties, and the continual insistence by many of his producers on removing him from his own movies, his track record as a director is outstanding.

His 1942 movie

The Magnificent Ambersons, despite being mauled in his absence to the extent that he claims the entire point has been lost, remains a fascinating and unique movie that's essential viewing even in its current form. Based on a book by Booth Tarkington that's really only remembered now because of the movie, it tells the story of the changes that technology was bringing to society as mirrored through the downfall of a wealthy family and, in particular, the insufferably self-centered and arrogant boy who seems to be their last heir.

The essential book

This Is Orson Welles contains an attempt by film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum to reconstruct what the original cut might have been like. Based on this, the loss of Welles's original version might be the greatest artistic tragedy of the 20th century.

The Stranger, from 1946, was Welles's attempt to create a purely commercial movie. It's a thriller in which he stars as a Nazi war criminal hiding out in small-town America, but even with this generic story and his determination to please the box office Welles was still able to include some fascinating touches. It's a shame that he was unable to convince the studio to let him cast Agnes Moorhead as the Nazi hunter doggedly pursuing his character, though Edward G. Robinson does fine in the role. A lengthy prologue involving the villain's escape through South American was cut, which Welles claims was the best part of the movie. It's a little more bland than the rest of his oeuvre, but still fascinating, and it went so far as to use actual footage from concentration camps to illustrate the evils of Fascism - the first movie to ever do this. In another director's hands this might have seemed exploitative, but as handled by Welles it seems completely responsible.

The movie was his only box office hit - though it should be noted that both

Citizen Kane and

Touch of Evil did very well in the few theatres they were shown in, despite severe distribution problems specifically designed to make both movies fail (a sadly frequent occurrence in Hollywood, believe it or not).

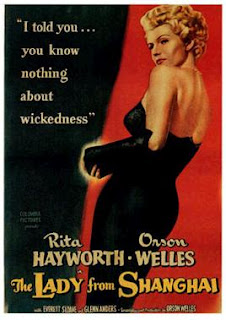

It was probably because of this success that Welles was easily able to find financing for 1947's

The Lady from Shanghai, a dark and baroque film noir in which he co-starred with his recent ex-wife Rita Hayworth. His cinematic technique is magnificent in this movie, which features an astonishing and nightmarish "hall of mirrors" ending that has been copied many times since, but producer Harry Cohn had about an hour cut from the movie before its release and this footage has long been lost. The movie was made mostly to help finance a gargantuan stage musical production of

Around the World in 80 Days that Welles was working on at the time, into which he sunk (and lost) a lot of his own money. This was to become a pattern in his filmmaking career, as his artistic goals continually trumped commercial concerns.

In 1948, Welles dramatically dropped his budget when he convinced Republic Pictures (who usually made Westerns) to finance a film of

Macbeth, the first of three astonishing Shakespeare adaptations he filmed. Welles had a life-long obsession with Shakespeare, editing & publishing several extremely popular abridgements under the umbrella title

Everybody's Shakespeare while still in his teens. In fact his first big success was a stage production of

MacBeth in Harlem with an all-black cast, which is #1 on my list of 20th century stage productions I wish I'd seen (a brief snippet was seen in a newsreel at the time, and it looks incredible).

Unfortunately the movie of

MacBeth was hampered by poor rented costumes, all they could afford on the tiny budget. Welles himself came off the worst; as he himself has noted, in some scenes "I looked like the Statue of Liberty," and in others he seemed to be "wearing a foot stool on my head." The result was unintentionally comic. The movie was also redubbed and cut after the fact (just this once at least Welles was able to supervise the changes himself) largely because the producers felt that nobody would understand the Scottish accents. Luckily, the original version has long been reinstated and Welles's preferred soundtrack is now the standard. MacBeth is easily the weakest of Welles's Shakespeare movies, but it is magnificently dark and many scenes are astonishing.

Welles was so disillusioned by his Hollywood experiences at this time that his next movie was made completely independently as far away from America as possible. Shot in Morocco and Italy over a prolonged period, and financed mostly by movie roles that Welles played during this time (to the extent that he would sometimes leave the cast on location - staying in luxury hotels at his own expense - to quickly shoot a movie role and raise some money), his version of

Othello went on to win the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1952. It's an astonishing achievement all around, and the first of Welles's movies largely made through extremely creative and innovative editing. Up until this point he was known for movies featuring many meticulously planned long takes, but the fast editing of

Othello must have been dizzying to 1950s audiences. Much of this was to cover the fact that the movie was made over such a prolonged period and in several locations, so that sometimes a single scene would have been shot in two countries, three cities and with gaps of several months.

Unfortunately Welles's daughter Beatrice, who inherited the rights to this movie, supervised a "restoration" of

Othello in 1991 where some dialogue was recut and the music was completely re-recorded. Most Welles scholars believe that this version has harmed the movie, and unfortunately it's the only version that's been available for almost twenty years.

The movie co-starred Michael MacLiammóir and Hilton Edwards, the two producers who had been the first to put Welles on the professional stage in Ireland in 1931, when he was only sixteen years old.

1955 brought

Mr. Arkadin, a movie so badly mangled by producer Louis Dolivet that for the rest of his life Welles hated to be reminded of it. It tells the story of a tycoon who hires a small-time crook to investigate his own past, ostensibly because he has amnesia but actually for much more sinister purposes. A bizarre, daring, dark and surreal movie, it originated in Welles's most famous movie role that he didn't direct himself, the brilliant Carol Reed/Graham Greene movie

The Third Man. This movie was so popular that Welles's character went on to his own radio show,

The Lives of Harry Lime, and two episodes of this provided the spark of inspiration for Arkadin.

Many people have attempted to put together what Welles's version might have looked like, culimating in an "integral version" released on dvd by the Criterion Collection in 2005, but we'll never know what he would have done with it if he had been allowed. What remains is a frustrating but (in my opinion) vastly entertaining pulp thriller, with so many versions (at least eight including the original radio version and the interesting novelisation published as by Welles but actually written in French by Maurice Bessy and translated into English by hands unknown). It's a fascinating jigsaw puzzle, hampered somewhat by a deliberately obnoxious lead performance by Robert Arden as small-time crook Guy Van Stratten but distinguished by a series of terrific, grotesque turns by a supporting cast including Michael Redgrave and frequent collaborator Akim Tamiroff.

After this heartbreaking disappointment, Welles fell into his next directorial role almost by accident. He was cast as the heavy in a B-picture to be called

Badge of Evil, but on the insistence of co-star Charlton Heston he was also hired as director. He agreed on the condition that he was allowed to completely rewrite the script, and the result is one of the great classics of late film noir: 1958's

Touch of Evil. Welles plays the grotesque Hank Quinlan, a corrupt and racist police detective in a town on the border between the USA and Mexico whose perfect record of convictions is the result of a lot of manufactured evidence.

The movie was taken from Welles during editing because the studio were unhappy with the rough cut, and he was barred from the studio. Until he died, he claimed that nobody ever told him what was supposed to be wrong with the movie. In 1998 a significant attempt at restoration was made, mostly by the brilliant editor and sound designer Walter Murch working from a 50-page memo sent by Welles to the studio in an attempt to salvage the movie. Murch was astounded to find that every single one of Welles's many suggestions worked in the movie's favour; he said that Welles's ability to keep the entire movie in his head (previously evidence by the production of

Othello) was almost super-human. This version is very good indeed, and includes some of Welles's most innovative sound design ideas, but once again we will never know what his version would have been.

This was the last movie Welles would make for an American studio, though for the rest of his life he longed to be able to work productively in his home country.

After some experiments in television, Welles was shown a list of books supposedly in the public doman by producer Alexander Salkind, and picked out Franz Kafka's

The Trial. The result is one of his favourite of his own movies, an astonishing waking nightmare about the nature of guilt and innocence. After designing elaborate sets, Welles discovered that Salkind did not actually have as much money as he'd claimed to make the movie, and managed to scout some incredible locations which he put to brilliant use.

Hard to enjoy (as designed) but easy to admire,

The Trial is almost certainly Terry Gilliam's major model for

Brazil and is loaded to the gills with great performances from Anthony Perkins, Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Akim Tamiroff (returning from both

Arkadin and

Touch of Evil and Elsa Martinelli. It's one of the great treasures of cinema.

Three years later Welles returned to Shakepeare with his best ever shot at filming the Bard.

Chimes at Midnight had started with an enormous production in the 1930s called

Five Kings where Welles had attempted to link all oft he history plays together in a show that took two nights for every performance. It was a huge failure and collapsed utterly before it could really be finished, but he kept the idea for many years, finally paring it down to tell the story of Sir John Falstaff as a tragic hero. Made on the sly while he was supposed to be concentrating on playing Long John Silver in Jess Franco's film of

Treasure Island (a movie that was never finished), it is Welles's most emotionally affecting movie. Yet another tiny budget and severe technical limitations barely hurt the movie, which boasts an incredible battle sequence that has been enormously influential on many later movies, and which features still more terrific performances from Sir John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, Jeanne Moreau again, Fernando Rey (a Spanish actor who is dubbed by Welles), and of course Welles himself in perhaps his best-ever acting role.

Tragically, this is one of the most difficult of Welles's movies to see as his daughter Beatrice has effectively suppressed it for many years.

Following another television movie,

The Immortal Story, Welles embarked on his most ambitious project yet:

The Other Side of the Wind. Only fragments of this movie have appeared over the years, as the final editing was ground to a halt after Welles was severely ripped off by someone who was supposed to be organising funding but ended up pocketing the money himself, and the movie was seized. The two major scenes that have emerged (both seen in the excellent documentary

Orson Welles: The One-Man Band, about all of his unfinished projects - of which there are many I haven't even mentioned) indicate that this would have been an astonishingly experimental and vivid movie.

While trying to complete his magnum opus, Welles was approached to narrate a documentary about art forger Elmer de Hory. While working on this, it was revealed that dr Hory's friend and biographer Clifford Irving was himself at the centre of a mammoth hoax involving a faked autobiography of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, and Welles was inspired to buy the footage from the documentary and, with the addition of new and old footage, make the incredible and still-unique "personal essay" movie

F for Fake. Almost impossible to describe or classify, this movie features Welles as himself and is about fakery, hoaxes and art, as well as being partly an autobiographical movie and a cinematic love letter to his partner Oja Kodar.

I defy anyone to watch

F for Fake and conclude that Welles was washed up after

Citizen Kane. It is overwhelming evidence that he was a vital, original, fabulous creative force throughout his entire life.

Welles's last completed movie,

Filming Othello, seems to be a more low-key and less innovative sort of "personal essay" movie, built around a monologu by himself and a filmed dinner with Michael MacLiammóir and Hilton Edwards. It was finished in 1978 and I am dying to see it.

Welles started but did finish at least five other movies that I have not mentioned here. He also appeared in dozens of movies directed by others, and had many more achievements besides. As well as directing numerous acclaimed and innovating stage plays from the 1930s until the 1960s, he was an accomplished stage magician (from entertaining the troops during World War II with his

Mercury Wonder Show to countless appearances on chat shows) and tried his hand at every kind of radio show going. At one point he made a concerted attempt to become a successful radio comedian; at others he concentrated on politics; other times he put together anthologies and almanacs, performed highlights from Shakespeare, and was very popular playing the pulp character The Shadow.

He also tried his hand at television, with everything from travel shows to educational shows to his own try at a chat show, which sadly usually only made it to "unaired pilot" stage.

Believe it or not, this has been a desperately brief and incomplete account of Welles's life.