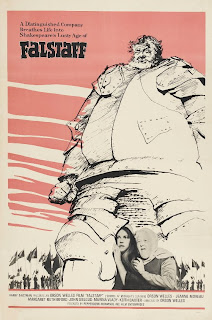

Chimes at Midnight is one of the best movies ever made. Unfortunately because of ongoing rights disputes it is a movie that has been very difficult to see for decades. Writer/director/star Orson Welles, working with a miniscule budget and an inexperienced crew, combined elements from five of Shakespeare's plays (

Henry IV Part 1,

Henry IV Part 2,

Henry V,

Richard II and

The Merry Wives of Windsor) as well as Raphael Holinshed's

Chronicles (the primary source material for Shakespeare's history plays) to tell the story of Falstaff.

Despite the abundance of no money, the technical limitations of his crew, and the fact that he basically stole the resources to make the movie when he was really supposed to be acting in an adaptation of

Treasure Island for another director, Welles managed to make a profound and beautiful movie that I regard as the greatest Shakespeare adaption I have ever seen. Welles was 49 when he made the movie, though with his makeup and padding he looks much older, and it is the most mature and complete movie he ever finished. It was the last feature-length fictional film he ever made as well as his last movie in black & white.

Part of the reason for the huge artistic success of

Chimes at Midnight is that it was a project Welles had been working on for over twenty-five years. It started as a stage production in 1939, when he was 23 years old and two years before

Citizen Kane. That production, which attempted to adapt Shakespeare's full history cycle as one mammoth production, was his first spectacular failure. Welles previously had been very successful with two landmark Shakespearian productions, a version of

MacBeth set in Haiti with an all-black cast and a version of

Julius Caesar set in facist Italy, but his tendency to try and outdo himself with each successive project finally got the better of him with this one. Eventually by 1960 he had pared the material down to focus on John Falstaff, usually portrayed as a clown but reinterpreted by Welles as a noble and ultimately tragic ruffian who

he described as "the most completely good man in all of drama." It's a curious statement about a character who is a drunkard, a wastrel and a thief, but Welles is very sincere in his affection for Sir John.

The interview with Welles linked to above is one of his best, and his description of the themes of the play relating to death is very instructive:

I can see that there are scenes which should be much more hilarious, but I directed everything and played everything with a view to preparing for the last scene, so the relationship between Falstaff and the Prince is no longer the simple comic one that it is in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part One, but always a preparation for the end. And as you see, the farewell is performed about four times during the movie, as a preparation for the tragic ending: The death of Hotspur, which is that of Chivalry, the death of the King in his castle, the death of the Prince (who becomes King) and the poverty and illness of Falstaff. These are presented throughout the film and must darken it. I do not believe that comedy should dominate in such a film.

Chimes at Midnight is a very difficult movie for me to write about. It's my favourite movie by my favourite director, and it's also my favourite Shakespeare adaptation. I feel like my knowledge of Orson Welles's filmography and other work is more than sound, but my knowledge of Shakespeare's history plays and their sources is much more shaky.

My blog posts on

Chimes at Midnight, therefore, will serve to help me sort out my feelings for the movie and for the character, and maybe they will help to nail down exactly why I feel such a strong affinity for Welles's work.